- Home

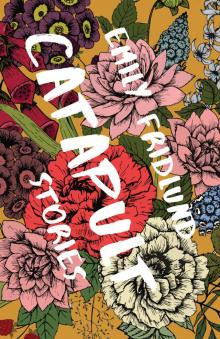

- Emily Fridlund

Catapult

Catapult Read online

Copyright © 2017 Emily Fridlund

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fridlund, Emily, author.

Title: Catapult: stories / by Emily Fridlund.

Description: First edition. | Louisville, KY: Sarabande Books, [2017]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017002604 (print) | LCCN 2017007179 (ebook) | ISBN 9781946448064 (ebook)

Classification: LCC PS3606.R536 A6 2017 (print) | LCC PS3606.R536 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017002604

Interior and exterior design by Kristen Radtke.

Sarabande Books is a nonprofit literary organization.

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. The Kentucky Arts Council, the state arts agency, supports Sarabande Books with state tax dollars and federal funding from the National Endowment for the Art

for my family,

who gave me love and art

Beauty is merciless and intemperate.

Who, turning this way and that, by day, by night,

still stands in the heart-felt storm of its benefit,

will plead in vain for mercy, or cry, “Put out

the lovely eyes of the world, whose rise and set

move us to death!” And never will temper it,

but against that rage slowly may learn to pit

love and art, which are compassionate.

—Mona Van Duyn,

“Three Valentines to the Wide World”

CONTENTS

Introduction by Ben Marcus

Expecting

Catapult

One You Run from, the Other You Fight

Marco Polo

Gimme Shelter

Lock Jaw

Time Difference

Lake Arcturus Lodge

Here, Still

Old House

Learning to Work with Your Hands

Acknowledgments

About the Author

INTRODUCTION

I wasn’t too many sentences deep into Emily Fridlund’s remarkable collection of short stories before I started to feel the strong pull of her intelligence. “It is easy to be wrong about a person you are used to,” says the narrator of “Expecting,” an eccentric portrait of familial survival. Such an admission might serve as a kind of motto for Fridlund’s work. She writes of families, marriage, and childhood as if our received wisdom—what we thought we knew about life and love and family—needs reparation. Fridlund charts, with a compressed, hurtling narrative style, the inner mythologies of her people, the logic and evasions and fears that guide and overwhelm them. This is fiction as excavation, peeling away the machinery of people and converting it to narrative. Fridlund shines a spotlight on what gets hidden and unreported, and the result can be overwhelming—cutting and funny and filled with difficult truth. Hardly a line goes by in these stories without some piercing bit of wisdom or destabilizing insight, and Fridlund does this with a light, swift hand, building stories of wit and misunderstanding and loss that are spilling over with seductive revelations.

A character from “Marco Polo,” speaking of his wife, says, “Once, on the Fourth of July, when our neighbors were setting off fireworks on the sidewalk outside our window, she looked at me and said, ‘You look like someone I’ve never met.’” Love is often misfiring in such a way in these stories. Fridlund is expert at tracking what happens when two people cannot calibrate their desire, when husband and wife, boyfriend and girlfriend, friend and friend, find each other strange, difficult, remote, impossible. Characters are isolated, bereft, looking out at a world that is increasingly beyond their control. The result, grim as it sounds, emerges as a kind of comedy. It is sadly funny to read of people whose insights remove them from safety, who are stuck inside cycles of thought that bear down on them and leave them exhausted. It is the very stuff of complex, necessary fiction.

When I finished the book I felt impressed with Fridlund’s range, but also her command of narrative tools, her control of the emotional atmosphere in a story. What a comfort, to read a writer so irrepressibly smart, so keen to achieve lines of prose that stun with their precision and insight. Her stories are free of inessential details, the kind of padding one too often finds in stories that bide their time until they no longer matter. This writer will make everything count, including the kind of data that is usually left for dead in a story. What is literary authority, after all, but the ability to regularly, without apparent effort, make the most of every sentence, to build feeling in every line and do it in such a way that is tough, tight, funny, and often brilliantly disruptive?

—Ben Marcus

EXPECTING

I.

My wife could take your skin off with one glance, she was that excruciating. She could call you to her with one finger. She could do long division in her head. Another thing she could do really well was sob, and I envied her this, assuming it left nothing to eat at her inside. It is easy to be wrong about a person you are used to. The day she left, she gave me an American flag packed in a clear plastic bag she broke with her teeth. I said, “What, you’re going to war?” And she said, “You always wanted something to hang from the porch.” She could be sweet and scornful at the same time.

A son is the same as a wife, save this confusion. These are the things my son will do: the laundry, the lawn, the bills. He has a head for numbers, like his mom, and figures our finances on spreadsheets. Kyle is nineteen, and it seems like the age he’s been all his life. I can hardly remember him being anything but lanky and bearded and morose. Periodically, his girlfriend Meg lives with us. She fills the freezer with cans of Diet Dr. Pepper that bulge threateningly—aluminum balloons—and burst. At night, I scrape tiny brown ice flakes from our frozen dinners. I heat the oven to 350 and arrange cardboard dishes on a metal cookie sheet.

“No au gratin potatoes, Darrell.”

I don’t know when it started, but my son calls me by name. He says, Darrell, there’s a call for you; Darrell, wipe your face. He says my name like it’s a kelly green suit, like it’s my botched attempt to be like other humans.

Because Kyle calls me Darrell, I call him Son. “Son, the potatoes come with the meal. You get what comes.”

“The smell of them makes me sick. Why don’t you eat them for me before I sit down? Come on, Darrell.”

He is standing in the doorway, his shoulders covered in a brightly woven throw. He is bare-chested, and I can see a few orange hairs flicker about his nipples. He has a five-pound dumbbell in one hand he’s been lugging around for weeks.

I take out the steaming dinners and spoon his potatoes into my rice. My son makes me unreasonably soft, like there’s a rotten spot in me only he knows about. I coax him to the table by setting out an open beer. When he sits down, he balances the dumbbell up on one end next to his elbow.

“Can you get my work socks in tonight?” I talk into my food.

“They can go with the towels, I guess.” He eats his chicken with a spoon.

We stay until the cardboard dishes start to collapse, then stand without speaking and throw our meals in the trash. We eat bowls of cereal. Kyle shakes a box of powdered Jell-O into his wide-open mouth.

For a few weeks after his mother left, I drove around the city on Kyle’s behalf, trying to find him a job. That was early summer, just after graduation, when the days were as long as they were ever going to get. I was afraid it looked bad to have an adult son without any plans. I brought home applications from Best Buy and Walgreen’s, each folded in half and tucked neatly in my lunch cooler. With my best handwriting and a new felt pen, I filled out my son’s personal information: Kyle Craige-Gryzbowski, no previous retail experience. I passed these papers to him shyly, barely look

ing in his eyes, my fingers damp from gripping the pen. Nothing came of this, which was a worry at first, then a relief. My wife used to call him Lazy Ass, but there is something comforting about Kyle’s laziness, the way a lolling cat can soothe your nerves. It pleases me to find him on the floor at the end of the day. He does halfhearted sit-ups and folds sheets. Sometimes, he’s just asleep, the TV shuffling its faces around, the night coming down, so slow and quiet I’d be a fool to complain. You don’t get many chances to be happy.

Of course, he can be difficult—not frightening like his mother, but frightened, which is worse. Try to see this: a six-foot man with a curly red beard who won’t come out of the basement. Kyle has respect for storms. On green summer nights, he holds a radio to his head and paces the sweating cement in his socks. I tell him, “Son, there’s no sirens. Come on upstairs.” But Kyle has a machine that calculates dew point and wind speed. He looks me in the face and says, “Fuck you, Darrell.”

On a night like this, I meet Meg at the back door. She is timid and avoids me by rubbing her eyes and yawning deeply: “God, I’m tired.” Her timidity also makes her polite, so she sits down when I tell her to. “Pears?” I hold out a squat, yellow can with a foolishly beaming man on the label. “Or fruit cocktail with cherries?” I shake the other can in the air.

“Maybe a little of both?” Meg runs the roller coaster at Mall USA, so she’s deft with people she dislikes. She is twenty and hasn’t seen her parents since she left Culver in the eleventh grade to get a job in the Cities. She treats everyone older than her like an employer.

Truth is, I usually regret making her eat with me. She slides her pears across her plate, leaving shiny, transparent trails. She picks the fibers from her oranges. When I ask her about her day, innocently enough, she tells me about a man who vomited out of his bumper car. “Hmm,” I say, clearing the plates. “Interesting.” I avert my eyes from her slippery fruit.

She says, “Sometimes I get sick too.”

“You coming down with something?”

“Well. I’m pregnant.”

It seems important to keep clearing our plates, to do this as long as possible. I take one fork at a time. I tend to the day-old crumbs on the table.

“Mr. Gitowski?” She says my name in a rush, like she’s trying to get past it to something else.

“Gryzbowski,” I say, but I hold off from spelling it out. Briefly, I think about my son downstairs, listening with all his machines to changes in the atmosphere. It would seem good and correct if the wind picked up, if the digits showing barometric pressure started falling. I believe that significant events should make some impact.

“G-R-Y-Z-B-O-W-S-K-I.”

“Isn’t that what I said?”

I am generous with her. “Maybe. I think so.”

She pushes out her chair, smiling with just her mouth. I suppose her line of work requires an official face. “Thanks for the fruit.”

After my wife left, I hung her American flag from a pole on the porch and tried to summon up some patriotic feelings. During Vietnam, I was always hoping my number would come up. I was working at a factory that produced party balloons, doing quality control in a great shuddering room that felt like a force of nature. They made me wear earmuffs and gloves. I looked for balloons without puckers, balloons without holes, until I was so bored and sad that war compared favorably. Back then, I was insulted by the kind of man who wore pieces of the American flag sewed on the cuffs of his jeans. I was Kyle’s age, nineteen, and I felt that killing someone would be less ghastly than selling sticky rubbers to kids. It wasn’t just about balloons. It was more that I wanted to die and war seemed the kind of place you could think that without being embarrassed.

The flag is wrapped around its pole like it decided to curl up for the night. I try to unwind it, but it’s caught, so I unfasten the pole from the house and take the whole thing inside. My wife would have scolded me for this. She had rules about indoor things and out; a flagpole in the living room would have made her distressed. She would have given me an exasperated look, a you-are-still-such-a-child-I-can’t-even-yell-at-you look before taking the flag and marching it back outside. This was the best and worst thing about my wife: she felt sorry for me. When I put my work boots on the mantel or fell asleep on her side of the bed, she’d groan and clench her teeth. She’d kiss me, long and deep, a sigh of disappointment.

She tried out her anger on our son. I remember when Kyle was small, she’d yell at him because he wouldn’t ride his bike in the summer. “Don’t you want to go out with the other boys?” She asked it over and over until it turned into an accusation. When he was a teenager, she put braces on his teeth, then threw her keys at him when he was too afraid to go to the orthodontist to get them off. I said to her, “All in his own time,” and she said, “Of course you don’t mind if your son’s a teenager the rest of his life.” She’d glance past Kyle and me into the reaches of the house, as if looking for someone more reasonable. She had a way of touching her lips with her fingers, pinching up a bit of skin and letting go.

In the living room, I unwind the flag from its pole, smoothing it on the floor. Spread out like that, it looks like something I should lay myself across—a bedspread, a beach towel. It looks like somewhere I should sleep. Meg comes home late from work. I hear her fumble through the kitchen, and I start to stand up, but she’s standing over me before I can go anywhere.

“Mr. Gryzbowski.” Her ponytail is cockeyed, and it makes her head look off, swollen out slightly over her ear.

“Oh. So, there you are.” I’m on my knees, gathering up the flag between my arms. “Good day at Mall USA?”

For a second I want to hide—this flag my wife gave me, my big body, my sullen American pride. I try folding the flag, but the cloth is slippery and uncooperative.

“People are stupid, you know?” Meg tugs out her hair tie, but her hair is greasy and stays where it was. “This guy? He tried to climb out of his seat in the middle of the ride. A grown man, and he’s up there with all these little kids hollering at the top of his lungs.”

“He was scared, right?” I drop the flag in a heap on the couch.

“Everybody’s scared. It’s a scary ride.” She runs a hand through her hair, then sniffs her fingers. “What makes him think he’s different?”

Soon Meg starts wearing shirts like hockey jerseys and eating all the best things in the house: frozen pizzas, Oreos. She watches football with me on Sunday afternoons and knows when to say “bump-and-run.” I like her better now than I did. She burps when she drinks from her soda can, popping up her eyebrows every time. She reminds me of my grandfather. She sighs like he did and rests her small white hand against the fly of her jeans. I suspect there is something different about her body, but I can’t say what. For a long time, it’s nothing you can see, just this look on her face like she’s swallowed something without chewing it first. Like she’s waiting to see if she’ll choke. Then one day she’s big as a boat, and it startles me to walk in the living room and find her moored on the couch. I have to keep myself from staring. I have to fasten my gaze on a clump of brown hair she holds between her teeth.

Meg spits out the hair and says nothing. She looks devastated by her body. I tell her she looks nice because I’m afraid for her.

“Oh. Well.” She doesn’t give me her official face. She smiles in a way that makes me think she hasn’t considered it first.

Then Kyle comes in—barefoot, wearing black biking gloves—and she turns official again. It’s not her Mall USA self, but a girlishness she assumes just for my son. She rolls her eyes at him when he wedges his way in between the armrest and her body. She nudges him with her elbow, managing to look—as teenage girls so often do—simultaneously superior and deprived.

Kyle rolls a hefty dumbbell onto her lap. “Lift it.”

“Whatever.”

Kyle is grave. “I’ve moved up to ten pounds. Darrell, you try.”

I watch Kyle drag the dumbbell off Meg’s lap. She s

ays he’s hurting her. He calls her a wimp. When he gets the thing in his hand, he purses his lips and squints his eyes in exaggerated exertion. They’re always acting like this, like they’ve been forced to sit next to each other in class and they don’t know whether they should fight or show off.

I say, “Let’s see you, Son,” but he sets the dumbbell on the floor and shakes out his wrist.

“Naw. I’ve done my reps already.” He pushes up his sleeve and flexes his bicep. “You can touch it, it’s real hard.”

I don’t know if he’s talking to Meg or me. We both reach out and poke at his arm, prodding the little lump awakened there. For a second I feel thrown off, as if Kyle is the pregnant one, and we’re feeling him for signs of new life. Then his fist trembles and he brushes us away.

“Oh, what a strong man!” Meg grabs at his hand as he tries to tuck it under his armpit. They wrestle for a moment on the couch, Meg reaching around the dome of her belly. Kyle is giddy and confident. It seems he’s worked all this out: Meg’s pregnancy, her need for him, her colossal body. He tries to shirk her off, and still she snatches at his arm, holding on till he cringes with pleasure.

For a few weeks at the end of the summer Meg stays with us every night. She takes half-hour showers after work and makes Dr. Pepper popsicles in the ice tray, milky brown cubes she sucks between her fingers. When she gets too big to share Kyle’s single bed, I offer her the one in the master bedroom. I stay in Kyle’s room, in a sleeping bag on his box spring, and Kyle gets the mattress on the floor. I’m in charge of dinner—I try casseroles now, Hamburger Helper—and Meg does the dishes because she says we leave spots. Kyle makes the shopping list. None of us takes out the trash. It molders under the sink, a dense, vegetable stink, until I eventually drag it out into the backyard. When I lose the toothpaste cap, Meg scolds me and Kyle backs her up, so I can’t tell anymore which parts we’re supposed to play: who’s the parent here, who’s the wife, who’s the child. In the evenings, we gather in the living room where we watch Nova and fall asleep. First Kyle, then Meg, then me, the universe on TV bending into flexible strings and vibrating softly.

Catapult

Catapult