- Home

- Emily Fridlund

Catapult Page 2

Catapult Read online

Page 2

II.

The thing about the baby is she isn’t a baby at all. We all see this right away. She is serious and disapproving, watching us blunder about her with bottles of formula, with nests of wet diapers. We take to hiding things from her. When we misplace her pacifier, we give her a toothbrush instead. We try to convince her that this is what babies do, suck on the bristly ends of little sticks, but the baby won’t bite. It’s not that we don’t like the baby, it’s that she doesn’t like us.

“Agg,” she says a lot, her face a grim frown of disappointment. She turns to us when we speak, listening with all her might for something she can endorse. She looks like a disgruntled old man, her ears red, her scalp bald and splotchy. Whenever I’m alone with her, she assesses my parenting with an intractable glare.

We’re out of clean spoons, and I offer her mashed peas from a fork, but she closes her lips primly.

“Come on,” I say. “It’s how everybody eats.”

She knows better. She knows that five-month-old babies have toothless mouths that are unsuited for metal tines. I find a wooden baking spoon, and she licks green mush from its tip grudgingly.

She’d make us feel better if she’d cry. When Kyle was a baby he used to scream in his crib all night, banging his elbows against the wooden bars and denying us sleep. We resented him in the usual ways, his mother and I, rolling our eyes and humoring him with songs about crowded barnyards. This baby humors us. Once, I found Meg bent over the crib, the baby’s onesie in a twist around her head, the baby’s naked body doing an underwater swim through Meg’s hair. Meg was crying and the baby was not. “I’m doing my best,” Meg defended herself, and the baby said, “Hmmm.”

I suspect that the baby has things to say she’s holding back. She parcels out a syllable at a time, polite baby talk, but her expressions are complex sentences.

For instance, she wrinkles up her nose at me, saying: Come now, wash your hands; use warm water and pat your fingers dry so when you touch my soft baby skin you don’t alarm me.

She clenches her jaw in the parking lot, saying: No sirree. If you leave me in my stroller while you pay the parking meter, who knows where I’ll be when you get back. I may consort with criminals. I may offer myself to kidnappers and feral dogs.

She is hardest on Kyle, though he doesn’t know it yet. When he holds her, he’s fond of moving her limbs up and down like levers. He cranks her arms, bending her elbows open and closed as if testing to see if she works properly. She looks at him like he’s an idiot, like he’s a very crazy man who must be indulged with the greatest of patience. When she can’t take any more, she puffs out her baby cheeks and drools on his sleeve.

“Agg,” Kyle says, using the baby’s language. He’s proud of her words and is always looking for contexts in which he can use them. “Blah.”

Kyle’s look of distaste is in fact a look of pleasure: the baby’s is real. She reminds me of my wife with this look, and I pray that the baby will never learn to talk, never wobble onto her feet so she can walk away. She disapproves of us, but for the time being there is nothing she can do. We take pictures of her, posed helplessly in our arms, while we can.

We call her “the baby” to her face to make ourselves feel better. Does the baby want upsie upsie? Is the baby a sleepyhead?

Once, we take her to the park so she can see everything she can’t do: climb the jungle gym like the neighborhood boys, wade barefoot into the lake with the little girls. We take her rowing in a rental boat, and I make a show of pulling at the oars. “Look at this,” I say, rowing fast and hard, propelling that boat across the pond until I’m wet with sweat and panting heavily. “Look at this,” Kyle says, standing up and waving his arms. He rocks the boat under his feet so we bob and toss through the green skim of milfoil. The baby, quiet on Meg’s lap, is unimpressed. For a few minutes she watches us in her bored and haughty way, and then she’s distracted by a goose hissing nearby. Look, look! I want to say, rowing the boat in circles around the lily pads, sinking the oars into the slick fronds so they come up laden. I want to say, You’re nothing at all, you’re eighteen pounds in someone’s arms, you’re a dead weight that would sink to the bottom of the pond and drift over carp and rotting cattails. I want to say, We’re all you got, but Meg talks first, saying, “I’m hot. I’m fucking dying.”

Kyle and I stare at her. We despise her for not even trying to look good in front of the baby.

Kyle says, “We still got twenty minutes with the boat.”

I say, “We’re just getting started.”

Meg rearranges the baby on her lap, hefting her up and putting her back like she’s considering her options. “Listen!” She sounds whiny. “I’m hot. I need to get the hell out.”

Kyle blinks at her. “Get out then.”

Meg turns on him. “We’re in a lake, what do you want me to do? I’ve got the goddamn baby.”

She seems surprised to find herself yelling, and the baby does too. They glance apprehensively at each other, like old rivals who’ve been pretending to get along for the sake of decorum. They both have their hands in fists.

When we get to shore, Meg deposits the baby in my arms so she can go buy herself an iced latte. She holds the waxed cup in one hand and a plastic straw in the other, spinning fast circles in the ice. Periodically, she tilts the cup into her mouth, the ice sticking, then sliding in a swift blow against her teeth. She lags behind on the walk back, chewing the ice and rim of the cup and the tip of the plastic straw. By the time we’re home, the cup is in shreds and she won’t go in the front door. She sits for a long time on the hood of her car, jiggling her heels against the bumper.

She bends the straw into an accordion and fits it in her mouth. I know she will leave soon and not come back.

Once when Kyle was a boy, my wife bought him a puppy, a Rottweiler mix with crooked ears. At first it was just a drooling, piddling, wiggling lump, but its development was so fierce that within a week it knew to sit for its food and wet the papers by the door. Within a month it was rolling over on demand, and it seemed that its education could go on and on, that it could learn anything we chose to teach it. It seemed the puppy became a dog so fast that it might become something else after that: a circus performer, a kindergarten student.

A human is different. A human lies there in your arms, month after month, feeble, sucking her own fingers. A human baby stays a squirming lump of flesh—uncoordinated, uncooperative—and needs you to lug her around and fill her with food and scrape excrement from her thighs. A baby stays this way so long, it seems improbable that she will be something else anytime soon, impossible that she will grow long and thin, her bones knobbing out from under her skin, her legs capable of carrying her. It seems unlikely that she will ever be anything but passive, inert, yours.

III.

Kyle tucks the baby under his arm and carries her around the house. He sets her up on the table when he’s writing out the bills, giving her a ballpoint pen which she bangs against her knee. He props her against the bathroom mirror when he brushes his teeth. He doesn’t lug around his dumbbell anymore, not since Meg left for design school in Duluth, not since the baby works just as well for building up his muscles. He balances her little bottom on his palm and raises her high above his head. When she wobbles up there, he makes a grab at her with his other hand and brings her gracefully into his chest.

In the kitchen, Kyle slides the baby around in a laundry basket—over the crinkly linoleum and under the table, where she drapes herself in his undershirts while he finishes his lunch. He stuffs his whole sandwich in his mouth, bulging out his eyes, peering down at her in her blue plastic cage. He puffs out his cheeks and sprinkles a few crumbs on her face, trying to impress her.

“Agg,” he murmurs through his food, doting, adoring. “Agg agg, hmmm.”

“Wow,” the baby says.

“What?”

“Wow.”

The baby has never used an English word before, and Kyle regards her with alarm. He lo

oks at her like she’s cursed him, like she’s making fun of him, like she’s a defiant puppy that’s learned to talk.

He swallows hard, wiping his face. “Honey, it’s me. I’m the baby’s Daddy.”

And the baby says, all sarcasm and scorn: “Wow.”

“Darrell?” He looks up at me, sitting with my Velveeta sandwich across the table.

I do my best to reassure him. “It’s just another sound she makes. She has no idea what she’s saying.”

It only happens once. We lose the baby somewhere in the house. She crawls off when we’re watching Nova and we spend twenty minutes looking in closets and under beds. She’s just a baby: she has stout, flabby arms and legs she drags around like an amphibian sea creature. There are no pads on her feet—just soft, pink flesh—and still she manages to get away.

Kyle loses his head, rifling through the laundry basket and tossing boxer shorts across the room. He puts his face in the baby’s Winnie-the-Pooh pajamas like he’s a dog taking in her scent. He wraps the pajamas around his neck and stalks down the hall and back, too upset to look for her effectively.

I search as methodically as I can. I pluck back the curtains and check behind the couch, pressing my palms into the carpet so they come up mottled. I sink my arms into the closet coats, into the wool and fleece, all those wintery fabrics closing in on me. Hangers catch against my throat. My wife could find anything lost, can opener in a baking dish, keys in a flowerpot. She’d know exactly where a baby would be, and she’d go there as well, to that secret place where no one else could find her. For a second, I think about how my wife looked the night she left for Tucson. I think about her sitting on the bed in her new green swimsuit, breasts sagging into points in the pockets of her bikini. She had goose pimples. When she smiled sadly, her lips whitened. A hanger clatters to the ground, and I fight past hoods and sleeves to the very back of the closet. I touch children’s snowsuits, clingy cocktail dresses.

I push out of the dark and try to be practical. I ask Kyle, “Did you check in the kitchen? In that weird corner of the cabinet?”

“You think she’s in a soup pot?”

“How about behind the radiator where the dog hid his balls?”

“Fuck you, Darrell.” Kyle presses the pajamas to his face. He strides up and down the hallway in his helpless way, as if the baby’s disappearance is a storm to wait out. I go into the bathroom to escape his dread.

And there she is. In the bathtub, standing behind the half-drawn curtain with its gray mildew blossoms. She has one hand on each metal faucet, tugging thoughtfully, humming to herself. She’s pulled off her diaper, and her bare ass is the same creamy white as the porcelain.

“Oh!” For an instant, she embarrasses me. I have an impulse to close up the shower curtains and let her go about her business. I have an impulse to back away and let her undress, let her draw her bath, soak her bald body in warm water, wash the dirt from her fingernails, shampoo the downy hair on her head, dress, call a cab, and get away. I say, “I’m sorry,” and she looks up, startled, distraught. She looks at me like my apology is not enough, my presence a disappointment beyond words.

Then Kyle swoops in and lifts her up under the armpits, so her face breaks. “C’mon!” she says, and I can see her considering her options: she thinks about kicking her legs, biting his cheek, pounding his arms. She decides to reason with him instead. “C’mon,” she suggests, pleading at first, then indignant. “C’mon, c’mon, c’mon.”

Kyle folds her into his arms, and though she struggles to sit up, to raise her head, he holds her on her back like she’s a newborn. “C’mon!” she says, but Kyle’s trembling all over and he will never listen to her.

IV.

Meg comes by on one of the last cold days of a very cold spring. The flag flicks in the wind, and my wife’s hyacinths bulge out of the ground like bumpy green grenades. Meg, in my doorway, has her fists in her jacket pockets, her hood blown up and flattened against her cheek. She looks for all the world like a little girl who’s come to ask my son to play.

“Mr. Gitowski?” she says, and I find myself nervous to see her. I hang my body in the doorframe, two palms against the cool wood, looking down at her as best I can.

“I—” She smiles in a flash. “I just wanted to see how everything’s going.”

“Right.”

“She’s getting really big?”

“The baby?”

“Yeah.”

I feel defensive. “She’s still little. You know.”

“Talking a lot?”

I sigh, closing my arms over my chest. “Some.”

Meg peers past me into the dark of the house. She unpeels the hood from her head, and I see a smattering of acne on her chin, red and glazed in a shiny make-up. “Can I see her?”

I hold my breath for a half second. “Well. Of course.”

Inside I tell Meg to wait by the umbrella hook. It’s where my wife used to have the UPS man stand, or the pizza boy when he came with a warm cardboard box balanced on a palm. Meg backs into the radiator and touches a zit on her chin with the tip of her pinkie finger.

I slip into the baby’s room and peer into her crib. She’s sleeping with her knees curled up against her chest, several strands of orange hair plastered to her forehead. She opens her eyes when I touch her, blinking blearily. She sits up, raises a hand to her head, and carefully brushes the hair from her face. She tugs her shirt over her exposed belly. When I pick her up, her legs swing down over my hips and bump the backs of my thighs.

Back in the entryway, I pass her over to Meg. “The baby. Here.”

“Oh!” Meg looks frightened by her. The baby hangs from her arms.

The baby says, “Agg.”

“Look at you!” Meg breathes. “You’re all grown up!”

And the baby—weary, worn out—says, “Come on.”

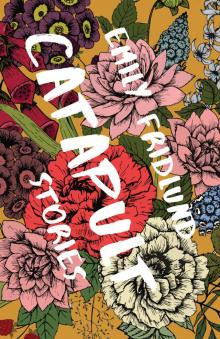

CATAPULT

That summer I was reading vampire books, so when Noah said no to sex, I let myself pretend that’s what he was. I told myself: inside his mouth is a hallway to death. That’s why his teeth are so wet, so flashy. Sometimes when he talked, I could see a white Cert floating over his tongue, flicking in and out of sight like the smallest of buoys. I wanted him to save me. I wanted him to save me from myself. It occurred to me for the first time that summer that I might have had a difficult life before I met him. There was a rusted yellow truck in front of my house; inside, painfully yellow linoleum. His house across the highway was neat as a table setting. He had a magical symmetrical family: mother, father, sister, terrier. He had a baby grand piano, a square of wallpaper in a frame, and a living room whose whole fourth wall was a mirror. Facing the back of the house, you could see the front door with its diamond glass, and through it, the well-intentioned geometry of streets upon streets.

Instead of having sex, we built a catapult in the grass. What else could we do? We were fourteen. Childhood was almost all we’d ever known. Every awkward pause brought us back to it. With relief, defeat, we sat on the driveway with the last Lego man in a Dixie cup. His face was just three dots—eye, eye, and mouth—and I remember thinking, What more, what more does anyone need? We launched three-dot man over the grass with wonderfully perfected, systematic, almost rote ambition. Over and over again. Childhood, by then, had been sucked dry by the unremitting soullessness of adolescence.

We’d met in class. In April, Noah had taken out a pencil and set it on the floor beneath my desk. It lay like a hieroglyph for me to decipher or ignore. It was too deliberate to be addressed, and I felt stunned by my advantage. I’d practiced for this moment of superiority all my life. In a hundred mirrors, I had looked out from under my shelf of bangs and said: You could never understand me. But when the bell rang, he stood up as if no such thing as a pencil had ever existed—as if pencils were the stuff of nerdy fantasy novels, of speculative documentaries—and, bewildered, humiliated, I touched his sleeve. “Is that yours?”

This made him tuck in his pants, which were already tucked. I coul

d see the misshapen wad of fabric beneath his belt that was the bottom part of his shirt. “No.”

“Yes,” I told him. My bangs were a roof, and I sat under them, waiting. I wanted him to admit that he was the one who laid the trap.

He held on tight to his backpack straps.

“You put it there,” I said. “You dropped it.”

“Want some lunch?” He took the pencil back. Like a good vampire living among humans, he acted as if he’d seen all this human work turn to wreckage before. He was patiently waiting it out, letting it crumble of its own accord.

At lunch I noticed his beautiful hands. Every time he lifted his sandwich, I could see his veins rise up and do a ghostly glide over his knuckles. By the end of the day, I knew he had a talent for math and a weird Charles Dickens brand of morality. He said to me, “Everything you think—it’s true. So think well.” I could hardly imagine what he meant by that. My mind felt like an intractable claw. Every thought was a secret wish to be better than other people. But Noah, I found out, had a well-organized heart. A mind full of unusual, ambitious thoughts, which he daily cultivated and tended. All spring we walked home from school together, discussing his theories. He wondered whether we could live without the moon—if, say, a meteor scraped it surgically, and without harming the earth, from the sky. Was it ornament or necessary? What were ornaments? What were necessities? What was surgery? What was harm?

“We’ve gotten used to the moon,” I said, by way of conclusion. “We can’t give it up.” Every once in a while, this could happen. A certain combination of words achieved by accident could make me feel expansive, luminous. Victorious.

He said, “Do we even look at it? Do we even care?”

“I don’t need to look at it. I’ve decided.”

“Don’t get mad at me,” he said.

Catapult

Catapult